A sense of honor is one of the simplest lessons our nation’s mightiest heroes can impart. But it’s a teaching we can absorb only by remembering better, by wielding our usable past.

This month marks the 114th year since Jose Abad Santos, the nation’s fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, passed the Bar Exams in October 1911. The occasion is an auspicious reminder, for we cannot avoid the subject of law given fresh revelations of plunder perpetrated, yet again, by the country’s so-called lawmakers, in connivance with criminals in the bureaucracy and private contractors.

Part of a storied family in Pampanga, at 10 years-old Jose Abad Santos served as a courier to the fledgling forces of the Philippine Republic during the Philippine-American War. His father, Don Vicente, was tortured and killed by Spanish authorities, who dragged his lifeless body from town to town to dissuade rebellious elements; his older brother was the radical intellectual Pedro Abad Santos who fought for the rights of the peasantry.

After the war, Jose would dive into studies in the United States where he obtained requisite degrees in law. He would return to the Philippines and serve “with distinction in legal positions, government services and on the Philippine Supreme Court as an Associate Justice, and finally as Chief Justice.”

Requested by Manuel Quezon in 1942 to join the government escaping the fast-closing fascist dragnet of the Japanese, Abad Santos declined and chose to stay. Quezon thus bestowed on Chief Justice Abad Santos powers equal to an Acting President of the Commonwealth, on top of his duties as Secretary of Finance, Agriculture, and Commerce.

Warned that “he might be captured and killed by the Japanese,” Abad Santos replied: “If such is my fate, I am ready to meet it; but in the meantime, I shall continue discharging the duties which the president has vested on me.”

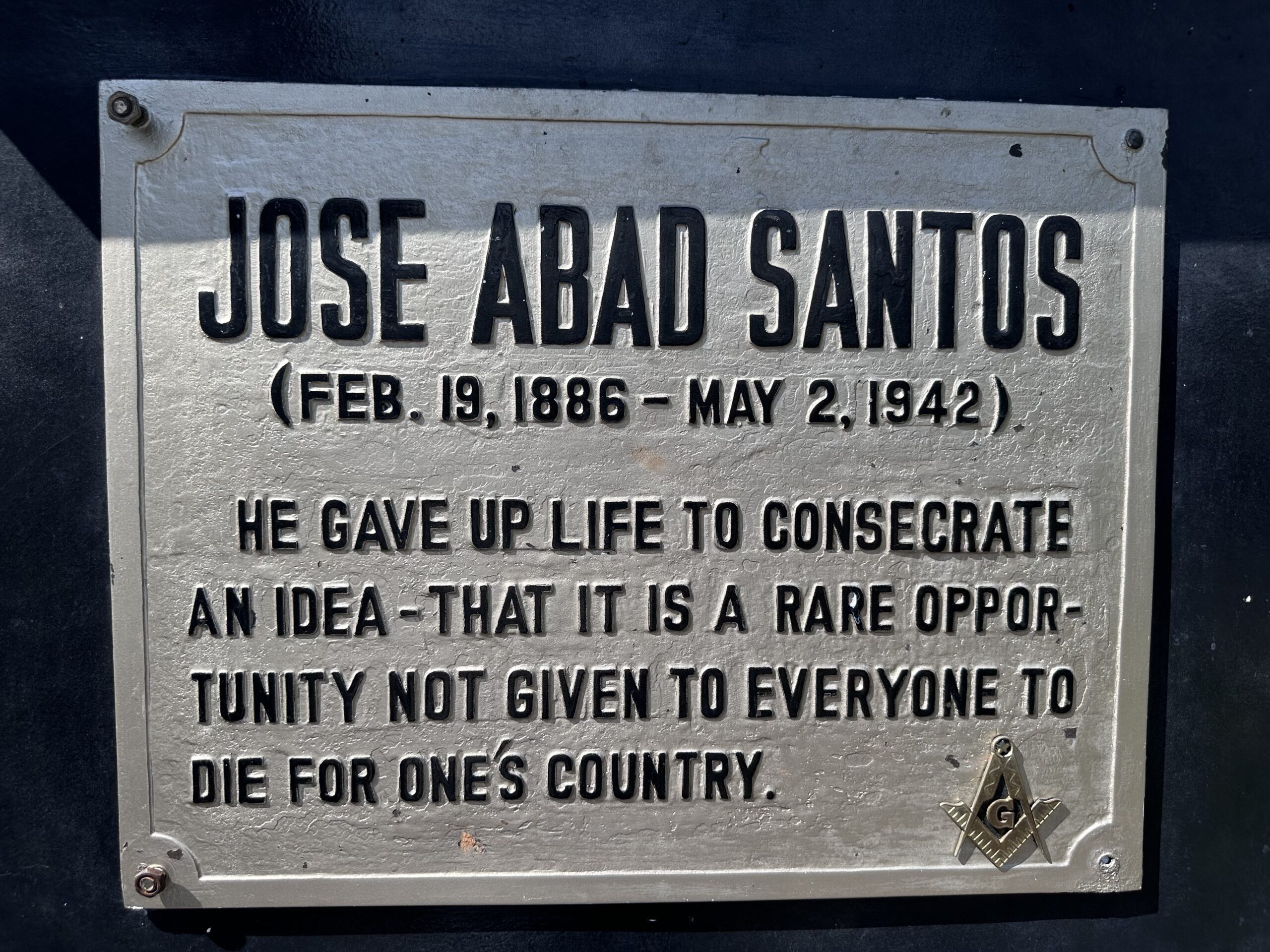

Abad Santos and his son Pepito were captured in Cebu by the Japanese on 11 April 1942. Ordered to swear allegiance to the Japanese Occupation, Abad Santos refused and was sentenced to death, though his son was spared. In Lanao del Sur, just before his execution by a firing squad, Abad Santos told his son not to cry: “It’s a rare opportunity for me to die for our country. Not everyone is given that chance.”

Abad Santos could have chosen exile and survival, but he chose honor instead of collaborating with the enemy. His was a choice that is today posed daily to officers of public office, from the president, vice president, legislators, down to the lowest government clerk. It is a choice to refuse collaboration with the enemy inside—those who offer the acid of ill-gained wealth that today corrodes all levels of public service. Because honor is not a mere costume worn only during wartime; it is a compass that should guide us every day. #JoseAbadSantos #Dangal #aPastRevisited #UsablePast #LahatNgKurakotIkulong

Sources:

“The Execution of Jose Abad Santos,” Official Gazette, https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/about/gov/judiciary/sc/cj/jose-abad-santos/the-execution-of-jose-abad-santos/

“Feb. 19, 1886: The birth of Chief Justice Jose Abad Santos, WWII hero,” Dennis Edward Flake, Philippine Daily Inquirer, 18 February 2025. See https://usa.inquirer.net/166685/feb-19-1886-the-birth-of-chief-justice-jose-abad-santos-wwii-hero

Image notes:

Photo of statue of Jose Abad Santos in Museo Ning Angeles, Pampanga, taken July 2024. ©ConstantinoFoundation

Photo of bust of Jose Abad Santos, undated sculpture by Guillermo Tolentino, from the National Museum, taken January 2024. ©ConstantinoFoundation